Concluding Black History Month: The Unsung Heroes

March 2, 2020

Black History Month is an annual celebration of the achievements and advancements of African Americans and their role in U.S. history. Also called African American History Month, this time set aside was from the early days of “Negro History week,” started by historian Carter G. Woodson in 1915. Since 1976, all U.S. presidents have recognized and designated the month of February as Black History Month with countries including Canada and the United Kingdom to follow.

For us generation Z kids, we have grown up with at least some passing mention of Black History Month each year. Some schools focus on just MLK day and others discuss it a bit more. February was Black History Month, and as in previous years, you often hear about Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr, and many more great leaders in the Civil Right Movement who paved the way for us to have greater equality for people of all colors before the law and in society. Along with these great sojourners, there are many unsung heroes that came before and after them: some that were enslaved, violently dealt with or lynched, or others who were never fully recognized for their work as inventors, writers, educators, and civil-rights leaders on their own merit. Some of these individuals inspired the leaders who are well-known from the Civil Rights era and their followers who are now carrying the torch.

I would like to list a few of these unsung heros and hope that these synopses encourage you to learn more about them and many others.

- Mary Ellen Pleasant, Abolitionist – slave in Georgia, freed in Philadelphia, indentured servant to a general store; she was all those things and more. She went on to become a wealthy woman in California and was known for bringing the Underground Railroad to California during the Gold Rush. She is most known for her victories in the courts, winning several civil rights cases that are still referenced today, giving her the moniker, “The Mother of Human Rights in California.”

- Matthew Alexander Henson, Explorer – born to sharecroppers who were freed slaves before the Civil War and inspired by Frederick Douglass; Henson was an American explorer who accompanied Robert Peary on at least seven trips to the Arctic over 23 or more years. The most famous expedition is the one where Peary reaches the North Pole on April 6, 1909. Henson was the core of these trips with his work developing relationships with the Inuits so they could use their help in their many treks across indigenous land. Some say that Henson was truly the first of them to reach the North Pole.

- Edward Bouchet, Physicist – born free, Bouchet reached the highest levels of academic achievement. He studied at Yale University and became the first black man to get a Ph.D. in the history of the United States at that time and the sixth American of any nationality to earn a Ph.D. in physics. Although he had received the highest honors possible in his field, due to racial discrimination he was not welcomed into the institutions to teach. He went on to teach at the Institute of Colored Youth for many years, leading the next generation of African Americans to reach beyond their potential in science and math.

- Lewis Latimer, Inventor on Thomas Edison’s Team – born to runaway slaves that later found themselves in Boston. His family was involved in the famous abolitionist case led by William Garrison where their slave owners tried to bring them back to Virginia. Latimer joined the navy as a teen, serving for a few short years. He found himself gainfully employed as an office boy with a patent law office and this job would change his life by giving him the tools to foster his desire to learn and develop his creativity. He went on to draw the patent application drawing for Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone. When Thomas Edison first invented the lightbulb, they were too expensive to become a commercial product at the time. Latimer later developed the filament system that made the lightbulb last longer and cheaper to produce. He went on to obtain many more patents in his lifetime.

- Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler, First African American Woman to receive a medical degree in the United States – She started her work as a nurse in Massachusetts and it wasn’t until the time of the Civil War that there was a need for women to pursue medicine to help with the care of veterans from the war. She was the first woman of color to be able to take on this great task. She served diligently and faithfully to improve the health of freed slaves in Virginia. She worked with the poor and destitute that would not receive medical care in underserved communities. She went on to publish the well known, “Book of Medical Discourses In Two Parts”, an early handbook on public health.

There are so many more individuals who have contributed greatly to our nation’s history and our lives today and I hope this article inspires you to research those that are not named in the usual history books. Look beyond! We can all be inspired and take pride in their achievements despite the adversity and obstacles they faced. I want to conclude with someone inspirational to me as well as many women in STEM, and honor her in her passing this past month: Katherine Johnson.

Johnson at her desk at NASA Langley Research Center with a globe, or “Celestial Training Device.”

Katherine was a pioneer as a mathematician and an unsung hero during the early days of NASA and our country’s exploration into space. She was part of the process and calculation of the first flight path of the United States’ manned space mission and later the moon landing. Her love for mathematics and numbers started at an early age when she graduated from high school at 14 years of age and went on to complete a college degree in mathematics. She was hired by NASA, along with many other African American women, to help with the computational math integral to the space program at the time. Her gifting as a mathematician and her unique understanding of what was needed was quickly noticed and she became an integral part of the team with her calculations becoming an essential part of the pre-flight checklist before any flights or missions. President Barack Obama awarded her the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, in 2015. “In her 33 years at NASA, Katherine was a pioneer who broke the barriers of race and gender, showing generations of young people that everyone can excel in math and science, and reach for the stars,” Obama said.

National Woman’s History Museum

Myra Pollack Sadker, A Washington educator and writer who led the efforts of recognizing gender bias in our nation’s classrooms. Credit: National Women’s History Museum

Reflecting on Women’s History Month: Public Education’s Largely Womanless History

Across America, young girls want and deserve to learn about their historical forebears in the same way that their male peers do. History teachers across the country take the time to laud the merits of the founding fathers, praise the policies of past presidents, and emphasize the cunning of military generals. Unfortunately for every student in that classroom and our modern education system, many, if not all, of the figures that their teachers will have taken the time to cover in detail will be men.

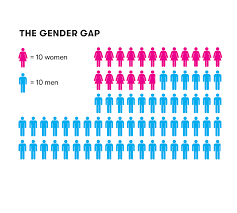

In the National Women’s History Museum’s report Where are the Women?, they analyzed each individual state’s educational standards and found that out of the 737 historical figures listed on standards just 178 are women. That comes out to about one woman for every 3 men students are required to learn about. Furthermore, 98 of those women were only on the standards for one state. The report found that this exclusion of women from state educational standards occurred as a result of the standards’ framework, which tends to prefer male-oriented leadership while over-emphasizing women’s domestic roles. The women in the state standards also did not reflect the diversity of the children who would be learning about them. It is clear that there is a severe underrepresentation of women in school curriculums which is not only a significant flaw in our national education systems but also distinctly impacts how students view themselves and others around them.

When we don’t learn about Jeannette Rankin, the first woman elected to Congress, Shirley Chisolm, the first woman to run for president from one of the two major parties, Katharine Johnson, who performed essential calculations for NASA’s spaceflights, or many others of the thousands of women who made significant contributions to American history, we not only neglect vital parts of American history but also perform a major disservice to students. When state standards ignore the accomplishments of women, students remain largely ignorant of their important contributions to history and society, thus perpetuating limiting stereotypes and confining gender roles. The prevalence of these stereotypes about the roles of women in history become abundantly clear when examining the women selected for the state standards. Over 50% of the women in the standards were recognized for their domestic roles, a number at least twice that of any other category including civil rights, suffrage, women’s roles in the workforce, and on the homefront, almost all of which in the single digits. It’s not to say that women’s achievements and contributions in the domestic sphere are in any way worth less, but the problem arises when they are disproportionately recognized and praised in comparison with other pursuits which men seem to dominate historically. Students rarely see women presented as historical leaders, innovators, and changemakers which can result (often unconsciously) in the underestimation of the abilities and potential of women, including themselves. Professor, author, researcher, and activist Myra Pollack Sadker once said that “each time a girl opens a book and reads a womanless history, she learns she is worth less.” I believe this to be true but, in the context of this opinion piece, I would adapt it to say “each time a student goes to school and learns a womanless history, they learn that women are worth less.”

Conversely, when women’s history and achievements are valued in education, this fosters greater self esteem in girls and greater respect among boys, according to the National Women’s History Alliance. They also state that this long term difference in perspective can lead to an increase in achievement by girls in school, a decrease in violence against women, and, on the whole, more stable and cooperative communities. It’s not to say that teaching women’s history in schools will permanently eliminate misogyny and sexism, but committing to recognize and respect the accomplishments of women through education would certainly be a step in the right direction.

Sources:

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/13/us/where-women-made-history-right-under-your-feet.html

https://www.womenshistory.org/social-studies-standards

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/what-schools-teach-womens-history-180971447/

https://nationalwomenshistoryalliance.org/why-womens-history/